In/Out management on Linux allows us to understand how data flows in Linux, from information coming from the network card, to the hard-drive, passing by CPU, RAM or others devices.

All systems will always be limited by their weakest link, or low-hanging fruit

We will try to understand how to exploit this architecture to manage bottlenecks.

Note: I’m using a Centos 9 stream which came out this month, only Linux will be covered here.

Definition

To make a computer work properly, buses must be provided that let information flow between CPU(s), RAM and others devices that are connected to the system.

Devices can be purely an input type (e.g. keyboard or mouse), an output type (e.g. printer, display screen) or both an input and output device (e.g. disk)

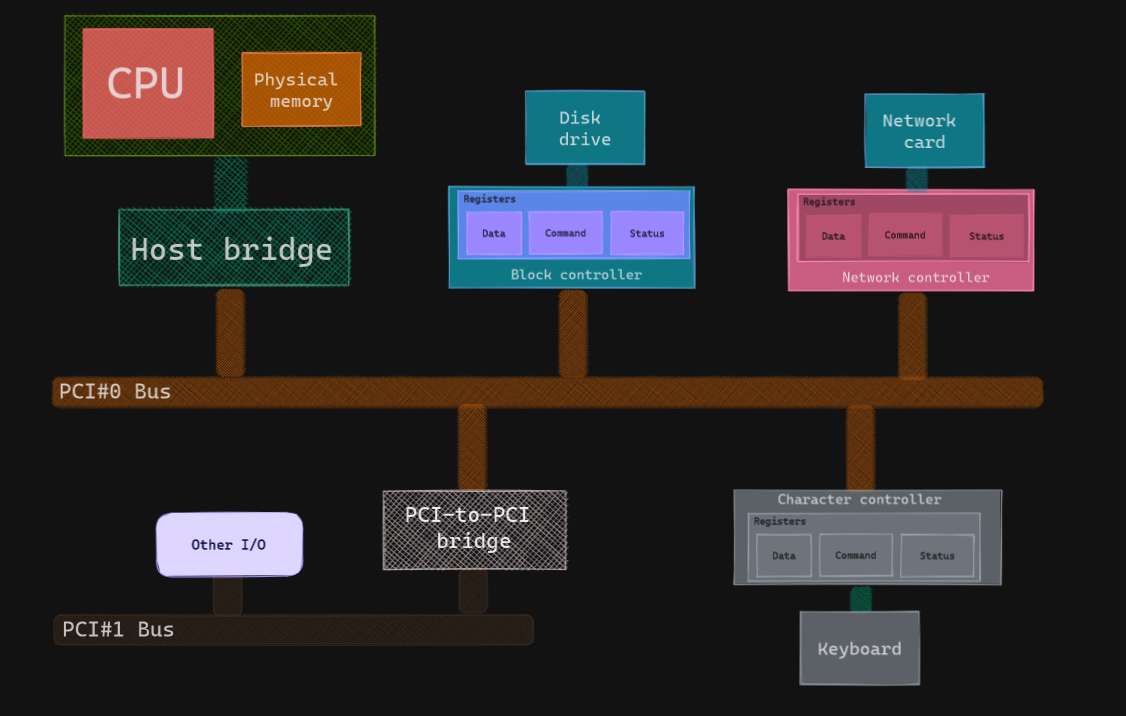

Regardless of their purpose, they must communicate through the system bus (e.g. typically the PCI), but they are not always directly connected to it. They can flow through interfaces first.

Interfaces were created to easen the CPU’s load to avoid having to understand and respond to each and every device. Also, sending signals on this system bus requires a very low electrical power, which makes the connecting cable very short (a few centimeters).

Interfaces are also called I/O controllers, and they typically holds three types of internal registers: data, command and status.

Besides the system bus, several other types exists, like ISA or USB, that communicate through bridges.

An image speak louder than words:

Here, the bus connecting to the CPU is often called I/O bus.

Concepts

Accessing I/O devices

It is possible to have direct control of any I/O devices through their controllers, but this would lead to a multitude of problems (unintentionnal or malicious). To avoid these problems, Linux provide routines to conveniently access those devices, made of system calls. Linux provides an API which abstracts peforming IO across all busses and devices, allowing device drivers to be written independently of bus type.

Each device connected to the I/O bus has its own set of addresses which are called I/O ports. The CPU selects the required I/O port and transfers the data between a CPU register and the port.

Memory mapped IO

I/O ports may be mapped into addresses of the physical address space. The CPU is then able to issue an assembly instruction (mov, and, etc.) that operate directly on memory.

It is the most widely supported form of I/O because It is faster and can be combined with DMA.

DMA was created for modern bus architecture, allowing an I/O device to transfer data directly from RAM. Only the CPU can activate this for each device and setup time is relatively high, but allows a device to be independent from the CPU after being authorized. It is mostly used by devices who need to transfer a large number of data at once.

There is synchronous and insynchronous DMA, the first is triggered by processes and the second by hardware devices.

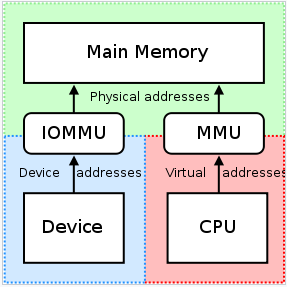

To go further, there is a memory management unit to connect I/O bus to the main memory, called IOMMU

It is notably used when running an operating system inside a virtual machine. It allows guest virtual machines to directly use peripheral devices such as Ethernet through DMA. AMD calls it “AMD-Vi” and Intel “VT-d”.

Devices drivers

A device driver is the set of kernel routines that makes a hardware device respond to the programming interface defined by the canonical set of VFS functions (open, read, lseek, ioctl, and so forth) that control a device.

Linux I/O

Now that we have seen how a device is considered from hardware to being present in the file system, let us see how a user can input and data with it !

A device driver acts as the bridge between the device (and its controller) and kernel modules. The main concept is a command should be device independent, we do not need to specify the I/O device to interact with it.

The way we can interact with those devices depend on its type, and there is a few to remember:

- Block devices, focusing on large data transfer (e.g. a hard drive)

- Character devices, focusing on small and quick data transfer (e.g. a network card)

- Clock devices, focusing on quick data access

One principle is to balance CPU, memory, bus and I/O operations, so a bottleneck in one does not idle all the others. One key aspect in controlling I/O speed is to control the number of context switch, but It comes with increased development cost and abstractions. Going from an application code running in userland to the device code (so It went through kernel, device driver, device controller) can take a long time (See ASIC or FPGA)

Useful commands

In order to find bottlenecks in our I/O limitations, we can try to use a few utilities packaged in Linux.

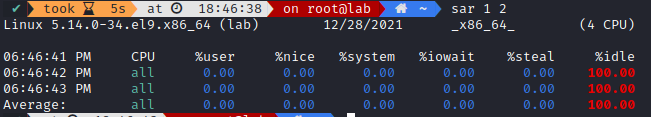

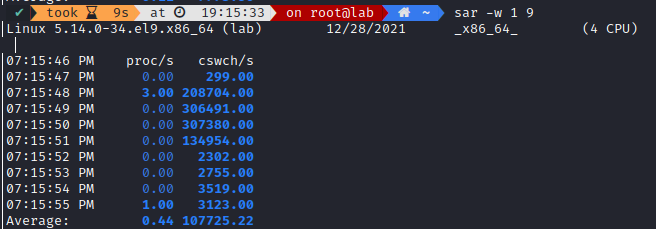

One of the best utilities is sar which collect most I/O activities

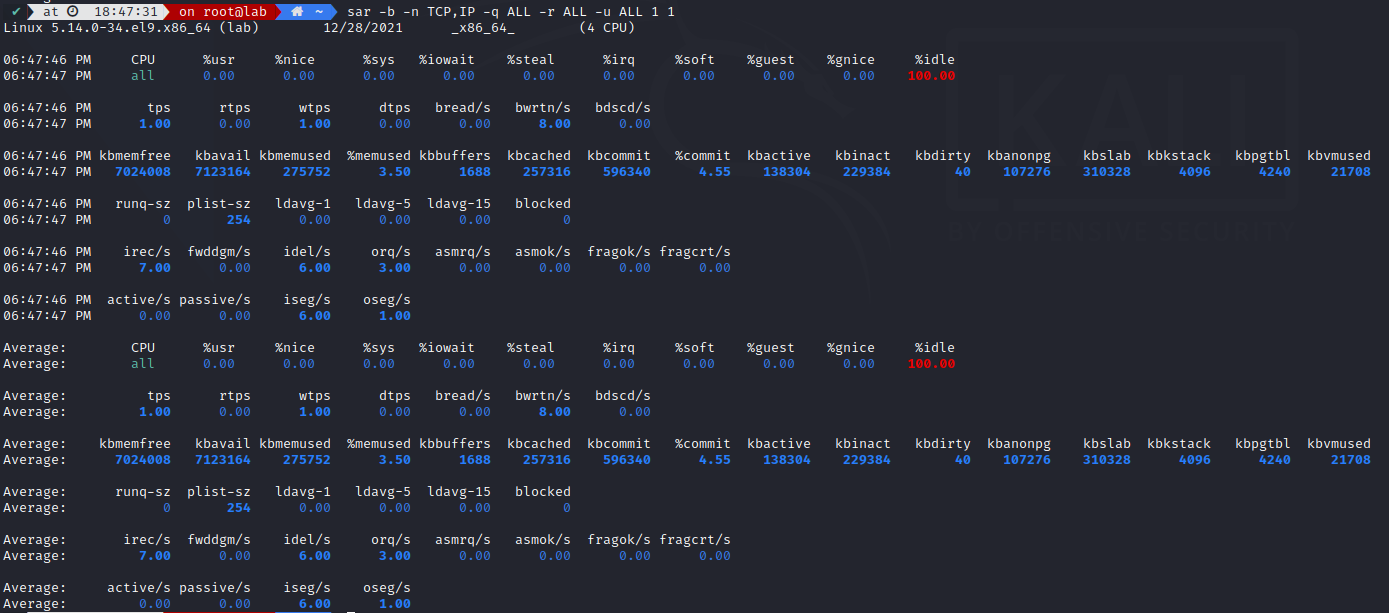

With more informations:

You will notice a lot of attributes, one metric is great at identifying bottleneck: iowait

It represents the percentage of time the CPU had to wait before reading or writing data.

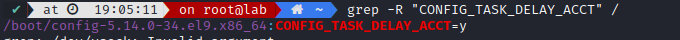

We can also use iotop to check those informations. However this type of information is not available by default, and It seems there is a kernel issue in the latest distribution, as enabling it does nothing. Using iotop -aoP would have shown us how much a process has written and read since iotop started, too bad.

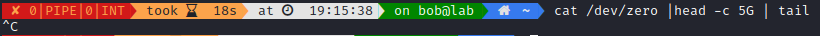

Let’s try a command that will flood the system, and see how It reacts

cat /dev/zero |head -c 5G | tail

Let’s check how many context switch we have when we use it

Here we can notice how It went up for 4 seconds (when the command was executed), as It needed time to move data across devices, but then went down once this data was transferred into memory.

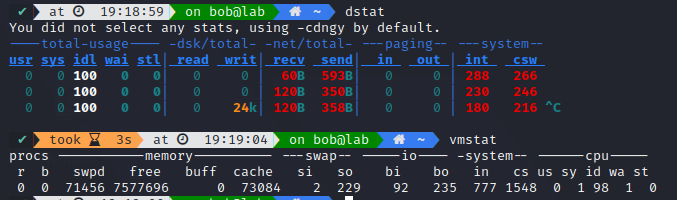

It can report statistics on network, CPUs, block devices and much more.

Multiple other utilities exists, like vmstat or dstat

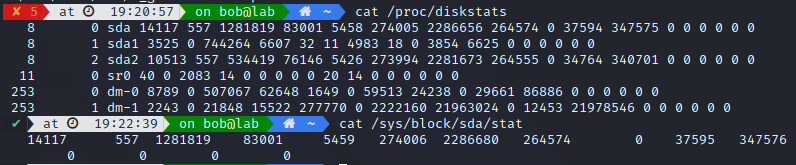

Or if you are feeling more adventurous, you can try to parse through /sys/block/sda/stat or /proc/diskstats

To go further

There is a LOT to explain on the bus/device controller/driver. I didn’t take the time to get through interrupt, polling and much more. I feel like I did not fully understand how bus works, as It’s hard to make the link between hardware and software, there is no visual to work from. I think I should have added notions of south and north bridge, but I don’t even know if they are still used or integrated into the CPU directly.

Check out the credits below, they are an excellent source of information to dive deeper into this subject.

Credits

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Input%E2%80%93output_memory_management_unit

https://doc.lagout.org/operating%20system%20/linux/Understanding%20Linux%20Kernel.pdf

https://applied-programming.github.io/Operating-Systems-Notes/8-IO-Management/#io-management

https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/understanding-the-linux/0596002130/ch13.html

https://www.kernel.org/doc/html/latest/driver-api/device-io.html

https://www.redhat.com/sysadmin/io-reporting-linux

https://unix.stackexchange.com/questions/55212/how-can-i-monitor-disk-io

https://haydenjames.io/linux-server-performance-disk-io-slowing-application/

https://www.linuxtopia.org/online_books/introduction_to_linux/linux_I_O_resources.html

https://www.slashroot.in/linux-system-io-monitoring