In this article we will talk about threads and writing programs with concurrency in mind. I will try to dive in the definition of threads, how they are used today, and the common pitfalls we can encounter.

Note: I’m using a CentOS 9 Stream which came out last month, so a few things might differ from your distro.

Definition

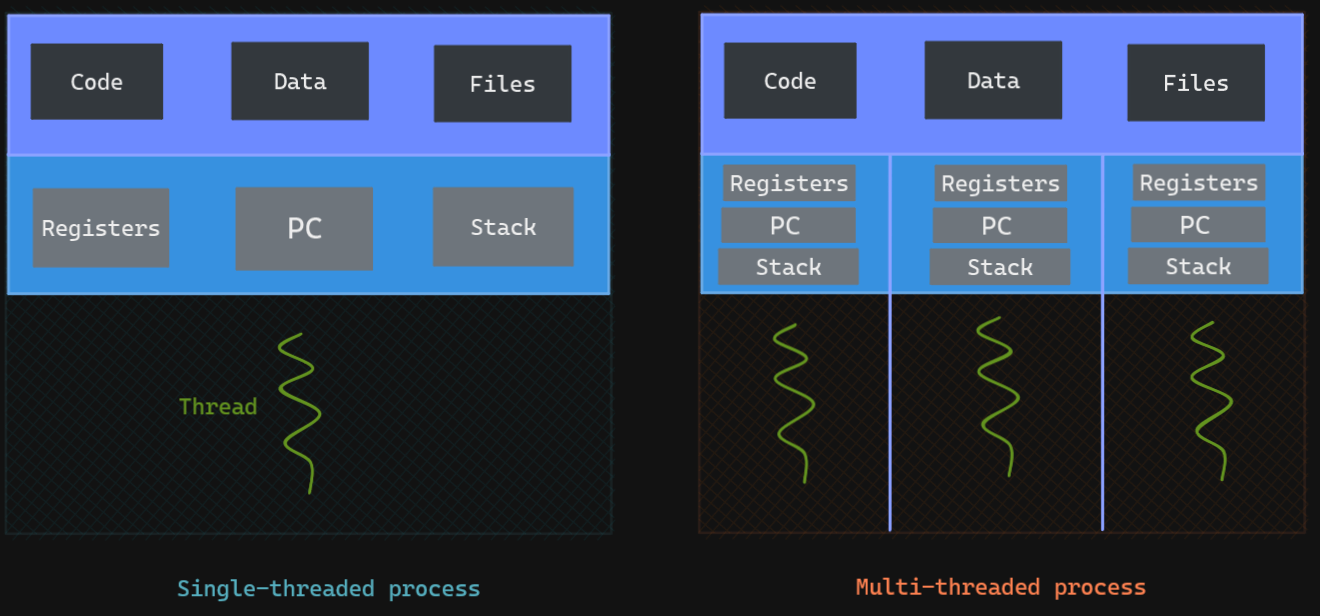

A thread of execution is the smallest sequence of programmed instructions that can be managed independently by a scheduler. In most cases, a thread is a component of a process. The multiple threads of a given process may be executed concurrently, sharing resources such as memory while different processes do not share these resources. In particular, the threads of a process share its executable code and the values of its dynamically allocated variables and (non-thread-local) global variables at any given time.

Popularity of threading has increased around 2003, as the growth of the CPU frequency was replaced with the growth of number of cores, in turn requiring concurrency to utilize multiple cores. Even today, finding programs which include multi-core support is rare.

A process is a unit of resources, while a thread is a unit of scheduling and execution. There is typically two types of threads: kernel and user. Kernel thread is the base unit of kernel scheduling, each process possess at least one, and owns a stack, registers and thread-local storage. User threads are the opposite, as they are managed and scheduled in the userspace, the kernel is unaware of them, this makes them extremely efficient at context switching.

Using a process is relatively expensive, as they own resources allocated by the operating system such as memory, file and devices handles or sockets. They are isolated and do not share address spaces or file resources unless you use an IPC. This is why threads are often preferred in case you need to often communicate in parallel (e.g. a GUI and its backend), they however increase the chance of bug since one misbehaving thread can disrupt the processing of all the other threads sharing the same address space in the application.

Implement threads

Now that we know what threads are, how do we actually implement them ? There is a few models that exist for Kernel/User threads, namely:

- One to One model: One user-thread is matched against the same kernel-thread

- Better for synchronization and blocking issues

- Bad for performance (thread limits is quickly reached, and kernel is required for each operations)

- Many to One model: Multiple user-threads are matched against one kernel-thread

- Better for portability, and less dependency on kernel thread limits

- Bad If one user-thread blocks a kernel-thread

- Many to Many model: have bound/unbound threads

- Best implementation

- Requires coordination between user/kernel thread managers (namely pool)

In order to understand them better, let’s study a few multithreading design patterns

Design patterns

We will first focus on a usecase where we receive a task, onto which we will apply a truly independent computation, and return the result. In the next part, we will try to understand how we can share this data, and perform thread-safe concurrency with lock and communication.

I will be using Go language, because why not. It’s possible to have finer tuning by using C/C++ kthreads.h library, in order to create kernel threads on the fly for example. But they are extremely hard to use because most native data structures (e.g. Hashes or Dictionaries) will break. This post explains it very well.

It is much easier to use user-threads (also called Green threads) as starter, as they are managed by your language, and chance are, they know what they are doing better than you (e.g. such as seeing partially-copied structure, transforming blocking calls into async). The best of both worlds is : use one OS thread per CPU core (since that’s your hardware limit anyway), and many green threads that can attach to any OS threads available. Languages like Go and Erlang provide this feature.

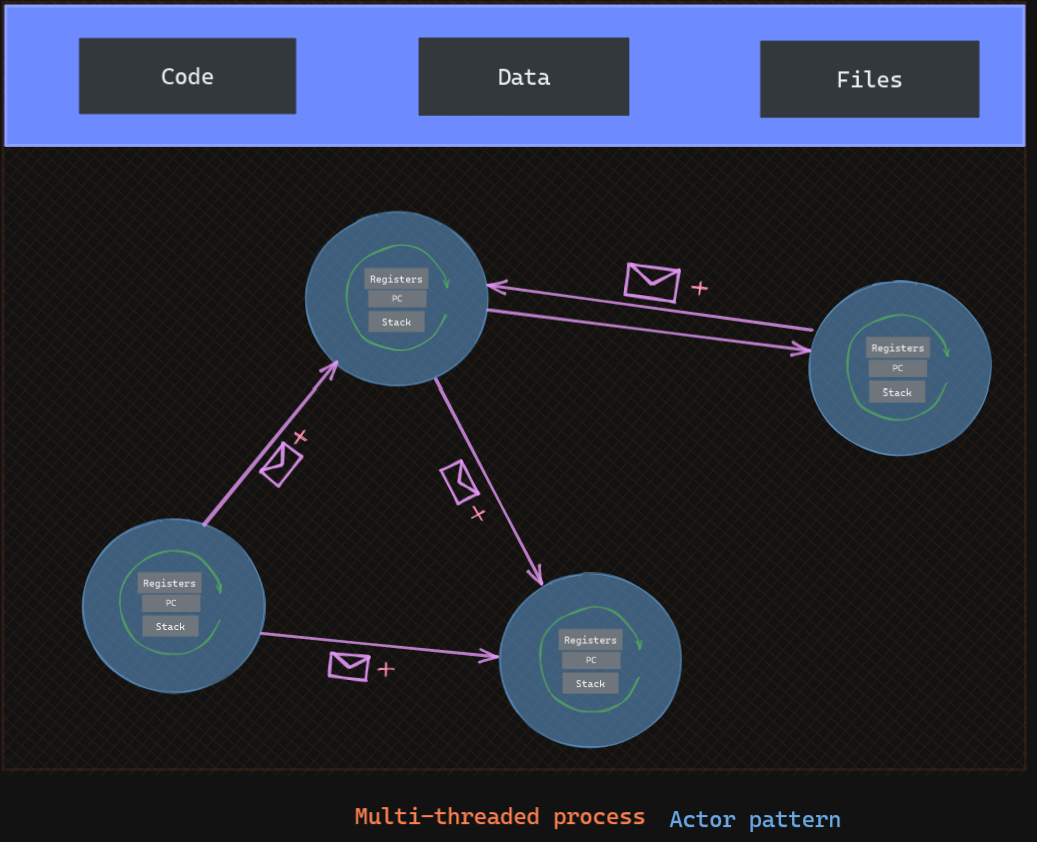

Actors-based pattern

In this model, each actor possesses a mailbox and can be addressed. They do not share a shared state, and when they need to communicate, they send a message and continue without blocking. Each actor will go through this mailbox and schedules each message received for execution. They also include a private state (occupied, etc.), and can make local decisions and create more actors.

It is used by Akka for example

Why use them in threads if they are not going to have a shared state then ? Because It will be able to execute asynchronously and distributed by design. It alleviates the code from having to deal with explicit locking and thread management. There is a few implementations possible, namely thread-driven actors and event-driven actors.

Boss/workers pattern

This model is more popular, as It depicts a single thread (the boss) that acts as the scheduler and create workers on the fly. It is used notably by NodeJS and NGinx as It is easy to implement on an Event-based program. The boss accepts input for the entire program, and based on the input passes off tasks to one or more worker threads. He’s often the one that creates them, and wait for each of them to finish. There is multiple implementations, with or without a thread pool.

Let’s create a simple program, which will receive a list of string, and return each bcrypt hash. Each hash calculation has to be done by an actor.

In the example, the iterative script takes ~ 50s to through 1000 words while the one with threads take ~ 100ms.

As you can see, having threads can reduce dramatically your execution time if you need to have independent calculations.

A few pointers on how to design them well:

- Identify truly independent computations

- Threads should be at the highest level possible (top down approach)

- Thread-safe data libraries is a must

- Stress-test your solution on multiple corner cases

Concurrency

In order to share data between threads, there is a few ways to communicate in a process, and It is often about picking one that best suits your needs.

It’s possible to use IPC (Interprocess communication) between threads, but that could be considered overkill. It still remains one of the solution you could use to effectively communicate. A few examples to name them:

- gRPC

- Signals

- Pipes

- Message queues

- Semaphore

- Shared memory

But a few mechanisms available only to threads exist, and It would be a shame to not use them.

Mutex

The first one is a sort of lock called mutex. Whenever the thread is accessing the data or resources that are shared among other threads, It locks a mutex so It can have exclusive access to the shared resources. The mutex usually contains a state (lock or free) and information about the thread locking it. What’s in-between the lock and unlock of mutex is called critical section, and that’s the place where you will safely access the resources. While It is a nice feature, you need to make sure your locking thread does not keep the mutex unavailable for too long, as It will make others threads unable to access the resource. This critical section needs to be as short as possible, as It is usually from where issues spawn.

The mutex also possess a list of others threads that tried to access it, as It avoids starvation, where one thread is able to continuously access the mutex when another is not able to due to scheduling problems.

This feature is often used in database, as It usually handles lots of concurrent access.

Atomic variables

A shared mutable state very easily leads to problem when concurrency is involved. While using a lock such as mutex is nice, and allow to run through a critical section without being afraid of concurrency, It usually cause waiting issues on other threads.

This is why atomic variables were created, in order to create non-blocking algorithms for concurrent environments. They ensure the data integrity by only allowing atomic instructions. These atomic operations focus on completing without any possibility for something to happen in-between, as they are indivisible and there is no way for a thread to slip through another one. There is no risk of data races, and allows better synchronization. They however are usually reserved for simple read or write of simple variables such as an Integer or String. If you need to concurrently access a file, a mutex would be fit better for this type of operation.

Message passing

Building a concurrent program is difficult, as It needs to take care of liveness (as less locks as possible) and fairness (each thread can process equally). A third type of communication is possible in Threads that tries to be as close as possible to these concepts is message passing. It can be implemented through several ways, but It is usually done in a synchronized queue. It re-uses the concept of producer-consumer pattern, but where each thread is able to be one or the other. The goal of the queue is to be as fair as possible, by including different scheduling with FIFO (First in First out) or FILO (First in Last Out). Each thread can implement a queue or they can share it through lock or atomic variables (pop and put).

All these features try to ensure Thread safety and make sure your program runs smoothly.

Pitfalls

A few common pitfalls stem from concurrent programming, and they come from the increased complexity of building a distributed architecture.

The first one is usually the deadlock where two threads block each other resources:

- Thread A blocks resource 1

- Thread B blocks resource 2

- Thread A needs resource 2 to unlock resource 1

- Thread B needs resource 1 to unlock resource 2

The only way to avoid this is to reduce the critical section to the least possible amount of resources.

The second one is race condition and It occurs when two or more threads can access shared data and they try to change it at the same time. Since you can not expect a specific order of execution due to the thread scheduling algorithm, you can not expect the change in data to be reliable as each thread will be “racing” to modify the data. The main issue is when a thread checks a value then act on it, even though another thread could have changed the value in-between.

Here, you would typically put a lock or use atomic operations to ensure the data integrity.

Third one is Starvation, where one thread occupies the majority of the execution scheduling, and It happens when there is no queue in place to ensure a thread does not wait too long, and increase in priority over time.

Last one would be Livelock, where two or more threads keep on transferring states between on another instead of waiting infinitely. It usually happens when you try to “replay” messages when a part keep failing, and they stick to repeating the same pattern over and over again.

Conclusion

While concurrent programming is difficult to implement, and harder to maintain, It is still interesting to see how It can speed up your process and make use of the multi-core architecture we are now always using.

The GO program was nice to implement, and the result is even nicer, and It really shows how good languages are getting at making parallel operations.

I think I should tried implement more pitfalls to showcase how they can happen, but I don’t think they are too hard to understand concept-wise. They usually happen when an application become more and more complicated, and can be devastating in some case.

Credits

https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/the-art-of/9780596802424/ch04.html

https://www.baeldung.com/java-deadlock-livelock

https://applied-programming.github.io/Operating-Systems-Notes/3-Threads-and-Concurrency/