In this article, we will talk about the different types of virtualization available on the market, how they are implemented and try to provide an explanation how their rise to prominence in the past 15 years. At the end, we should understand what is a virtual machine, hypervisor, container or jails and have an idea of what’s coming next.

Note I’m using a CentOS 9 Stream (released in Dec 2021) running on an ESXi 7.0.

Definition

Virtualization is the act of creating a virtual (as opposed to actual) version of something. It includes virtual computer hardware platforms, storage devices and computer network resources. While the term is broad, in our case It is mostly applied to a few different types, namely:

- Hardware virtualization

- Full virtualization

- Paravirtualization

- Desktop virtualization

- Operating-system-level virtualization, also known as containerization

We will explore each of them, and understand their usecases and differences. There is many more types which can be applied to IT/CS, but It will be explored in other articles, to name a few (with some examples):

| Virtualization type | Example |

|---|---|

| Application | Citrix XenApp |

| Service | Postman |

| Memory | AppFabric Caching Service |

| Virtual memory | Swap + RAM |

| Storage | disk partition |

| Virtual file system | CBFS/VFS |

| Virtual disk | .iso |

| Data virtualization | VDFS |

| Network | VLAN / vNIC / VPN |

Before we dive in the details, we can try to explain why It rose to such popularity in the recents years. By separating resources or requests for service from the physical delivery of that service, virtualization enables owners to distribute resources across the enterprise and use infrastructure more efficiently. This has been made evident with all Cloud computing platforms such as AWS, AZURE or GCP.

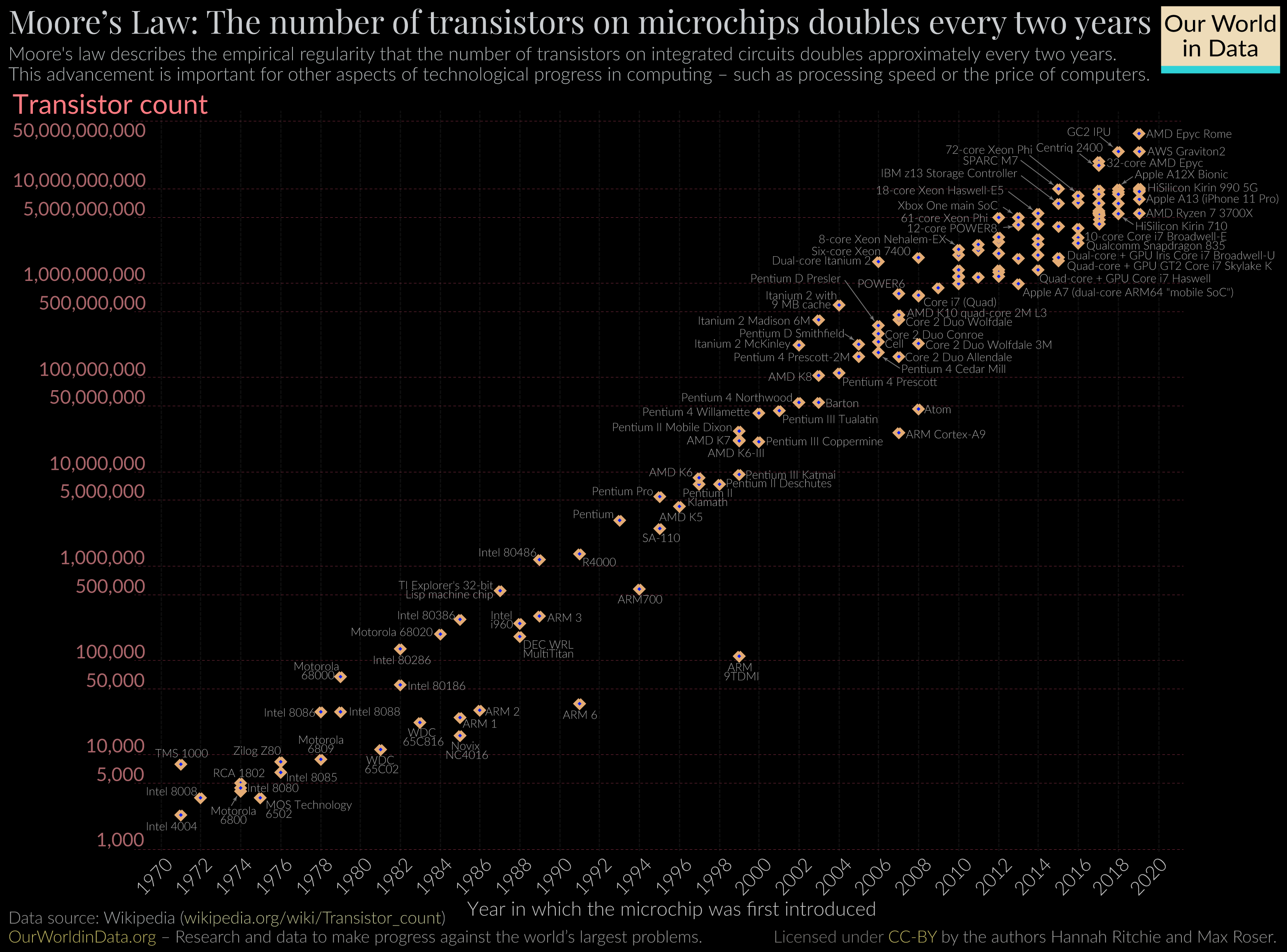

The rise of the service design patterns made it all the more effective under Moore’s law, where computing power was rendered cheap, and Internet bandwidth exploded (through fiber or 5G networks), all to have clusters outsourced.

Hardware virtualization

Hardware virtualization specialize in efficiently employ underused physical hardware by allowing different computers to access a shared pool of resources. There is a few components to note:

- The hardware layer, often called host, contains the physical server components, It can be CPU, memory, network and disk drives. It requires an x86-based system with at least one CPU

- The hypervisor creates a virtualization layer that runs between the OS and the server hardware, and acts as a buffer between the host and the virtual machines. It isolates the virtual components from their physical counterparts

- Virtual machines are software emulations of a computing hardware environment, and provide the same functionalities of a physical computer. They are often called guest machine and consist of virtual hardware, guest OS and guest applications

CPU virtualization emphasizes performance and runs directly on the processor whenever possible. The goal is to reduce the overhead when running instructions from the virtual layer compared to instructions on the hardware layer.

IOMMU infrastructure

Having a memory controller with IOMMU will speed up virtualization instructions by reducing the amount of context switch, resulting in little to no difference compared to running hardware machine. This is often advertised as Intel VT-d or AMD-Vi. IOMMU is what made it all possible. It is an unit which allows guest virtual machines to directly use hardware devices through DMA and interrupt mapping. Be careful on this, as while this is a CPU unit, It requires motherboard chipset and system firmware (BIOS or UEFI) support to be usable.

A note on SR-IOV - It is a chipset feature which allows scalability of devices on virtual platforms. In IOMMU, virtual devices are mapped directly to their physical devices for performance reasons, but It limits the number of virtual machine to your number of hardware devices. SR-IOV solve this by allowing splitting one PCI device to many virtual ones without performance drop via parallelized direct IO access.

IOMMU goal

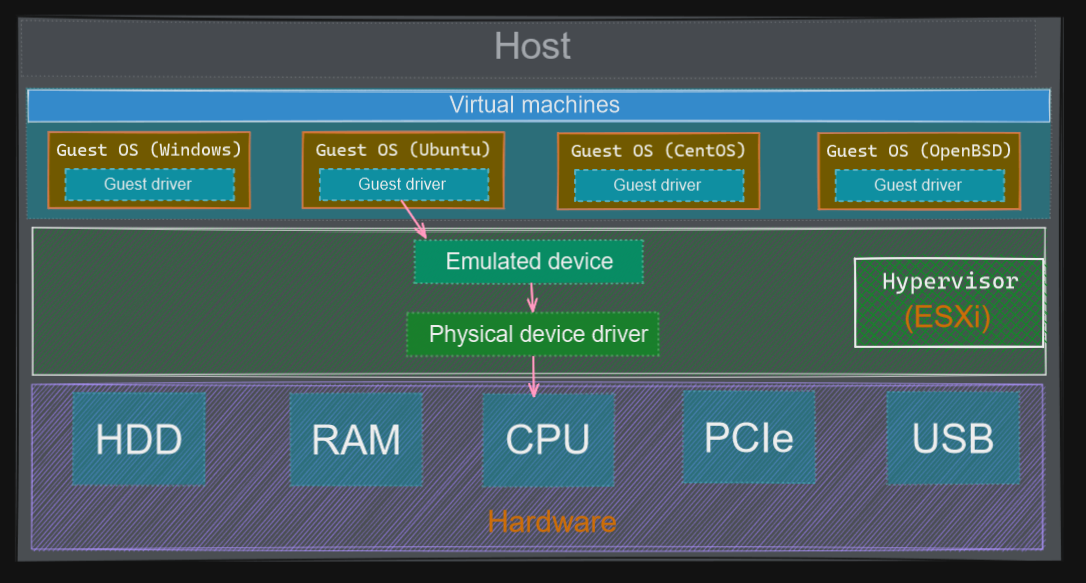

In a virtualization environment, the I/O operations of I/O devices of a (virtual) guest OS are translated by their hypervisor (software-based I/O address translation). It results naturally in a negative performance impact.

In an emulation model, the hypervisor needs to manipulate interaction between the guest OS and the physical hardware. It implies that the hypervisor translates device address (from device-visible virtual address to device-visible physical address and back), this overhead requires more CPU computation power, and heavy I/O greatly impacts the system performance.

The next figure illustrates it:

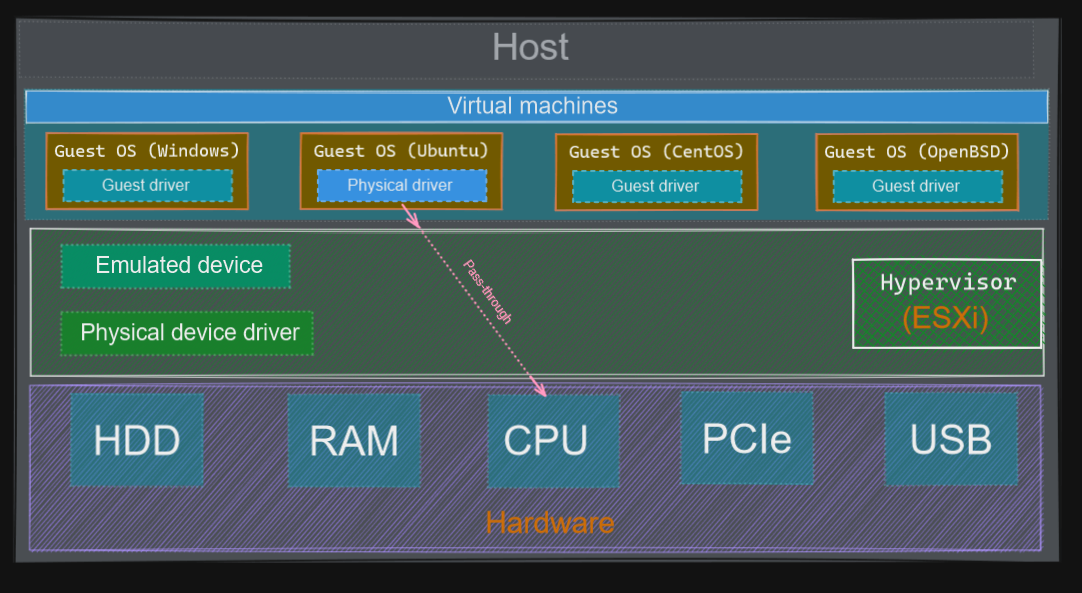

Next, we get into the pass-through model, where the hypervisor is bypassed for the interaction between the guest OS and physical device. It has the advantage of avoiding the emulated device and attached driver. Here, the address translation is seamless between the guest OS and the physical device.

The next figure illustrates it:

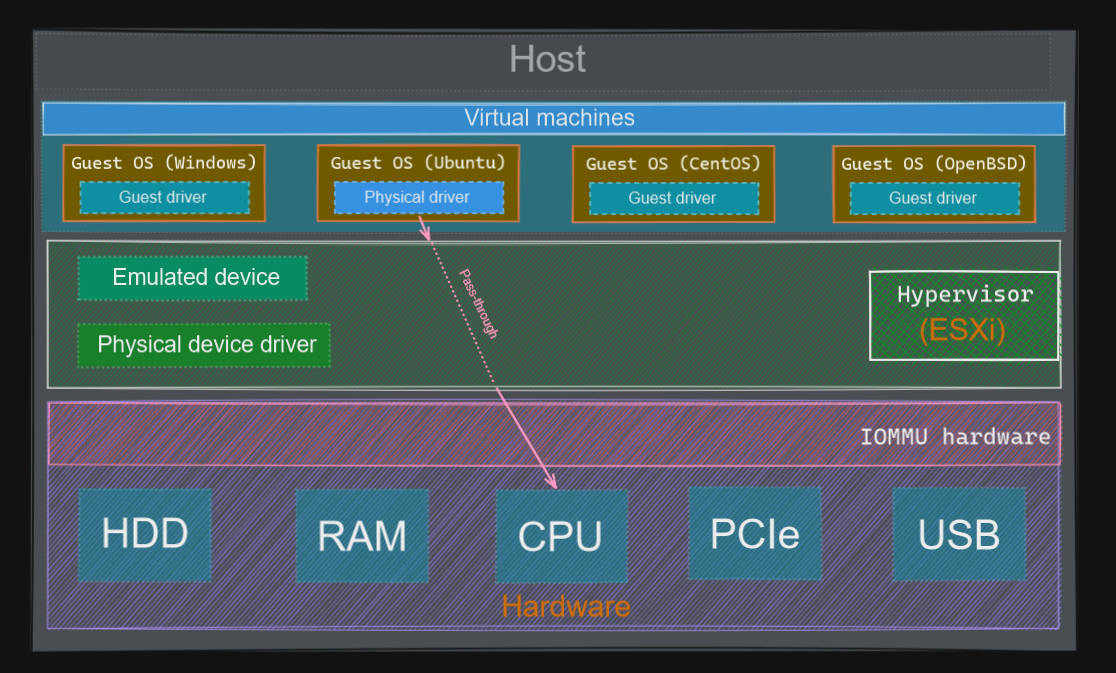

It is made available thanks to a hardware-assisted component called IOMMU. And It looks more like this:

There is two memory management units in a CPU:

- MMU (Memory management unit), to translate CPU-visible virtual address <-> physical address

- IOMMU (Input output memory management unit), to translate device-visible virtual address <-> physical address

In order to provide this feature, IOMMU provides two functionalities, DMA remapping and interrupt remapping.

IOMMU DMA remapping

In order to understand how DMA works, and why It is so effective, we need to do a recap of how memory works in our system.

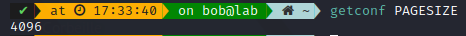

Physical memory is divided into discrete units called pages. Much of the system’s internal handling of memory is done on a per-page basis. Page size varies, but usually use 4kB pages.

This means that If you look at a memory address, virtual or physical, It is divisible into a page number and an offset within the page. One example will explain it more easily how paging works:

One note on TLB, since page tables are hold in memory, every data/instruction acccess requires 2 memory accesses (One for virtual address, one for physical address), and memory accesses are much slower than instruction execution in CPU. To accelerate the translation mechanism, a small fast-lookup hardware cache is added close to CPU, and this is called the Translation look-aside buffer or TLB, It contains the most common of the page-table entries. In the screenshot below, you will notice It is noted Huge, simply because 4KB is often not enough in today’s context, so we created bigger pages.

Now that we know how memory is translated from virtual to physical realm, let’s dive into the DMA topic. DMA, or direct memory access, is the hardware mechanism that allows peripheral components to transfer their I/O data directly to and from main memory without the need to involve the system processor. A great deal of computational overhead is eliminated as the use of this mechanism can greatly increase throughput to and from a device.

Without DMA, on any I/O operations, the CPU is typically fully occupied for the entire duration of the read and write operation, and is thus unavailable to perform other work. With DMA, the CPU first initiates the transfer then It does other operations while the transfer is in progress, and It finally receives an interrupt from the DMA controller when the operation is done. DMA does not only exist on CPU, but on many hardware systems such as disk drive controllers, graphics cards, network cards and sound cards.

On PCI architecture, any PCI device can request control of the bus and request to read from and write to system memory. One issue is often the size of the address bus, as It can be unable to address memory above a certain line, and that’s where the IOMMU comes into play with its previously seen address translation mechanism.

The idea of IOMMU DMA remapping is the same as the MMU for address translation.

IOMMU interrupt remapping

An interrupt is a response by the CPU to an event that needs attention from the software. It is commonly used by hardware devices to indicate electronic or physical state changes that require time-sensitive attention.

A MSI, or message signalled interrupts, are an alternative in-band method of signalling an interrupt. It allows devices to save up on an interrupt line (pin), as It uses in-band signalling to exchange special messages that indicates interrupts through the main data path. Fewer pins makes for a simpler, cheaper and more reliable connector. PCI Express only uses MSI for example as It presents a slight performance advantage.

Device can trigger interrupt by performing a DMA to dedicated memory range (0xFEE00000 - 0xFEEFFFFF on x86). This means a virtual machine can program device to perform arbitrary interrupts. Without it, IOMMU cannot distinguish between genuine MSI from the device and a DMA pretending to be an interrupt.

Full virtualization

Now that we understand how IOMMU came into play to enhance virtual machine performance, let’s check some relevant approach to virtualization technology.

In Full virtualization, hardware is emulated to the extent that unmodified guest OS can run on the virtualization platform. Normally, this means that various hardware devices are emulated. Such virtualization platform attempts to run as many instructions on the native CPU as possible (which is a lot faster than CPU emulation). Many of these platforms require CPU extensions to assist virtualization such as an IOMMU.

The hardware architecture is completely simulated, and the guest OS is unaware that It is in a virtualized environment, and therefore hardware is virtualized by the host OS so that the guest can issue commands to what It thinks is actual hardware. However, these are just simulated hardware devices created by the host, and the hypervisor translates all OS calls. It isolates VMs from the host OS and one another, enabling total portability of VMs between hosts regardless of underlying hardware.

It is often called type-1 bare-metal virtualization. It offers the best isolation and security for virtual machines. A few products to name them: KVM, ESXi, Hyper-V or Xen.

Paravirtualization

OS Assisted Virtualization is another approach to virtualization technology, where the guest OS is ported to the hypervisor, a layer sitting between the hardware and virtualized systems. Since It doesn’t require full device emulation or dynamic recompiling to catch privileged instructions, It is usually performing at a near-native speed.

While the value proposition of paravirtualization is in lower virtualization overhead, its compatibility and portability is poor.

It is often called type-2 virtualization. A few products use this technology, like QEMU, Xen, VirtualBox or VMWare workstation.

Desktop virtualization

While not as popular as full-virtualization, desktop virtualization is a method of simulating a user workstation so It can be accessed from a remotely connected device. By abstracting the user desktop in this way, organizations can allow users to work from virtually anywhere with a network connecting to access enterprise resources without regard to the device or operating system employed by the remote user. It skyrocketed to popularity during the COVID pandemic and all the work-from-home habits.

Since the user devices is basically a display, keyboard and mouse, a lost or stolen device presents a reduced risk to the organization. All user data and programs exist in the desktop virtualization server and not on client devices.

There is three types of desktop virtualization:

- Virtual desktop infrastructure (VDI) - either on-premises or in the cloud, It manages the desktop virtualization server as they would any other application server

- Remote desktop services (RDS) - runs a limited number of virtualized applications which are streamed to the local device, offers a higher density of users per VM

- Desktop-as-a-service (DaaS) - shifts the burden of providing desktop virtualization to service providers, depends on IT expenses/needs

Containerization

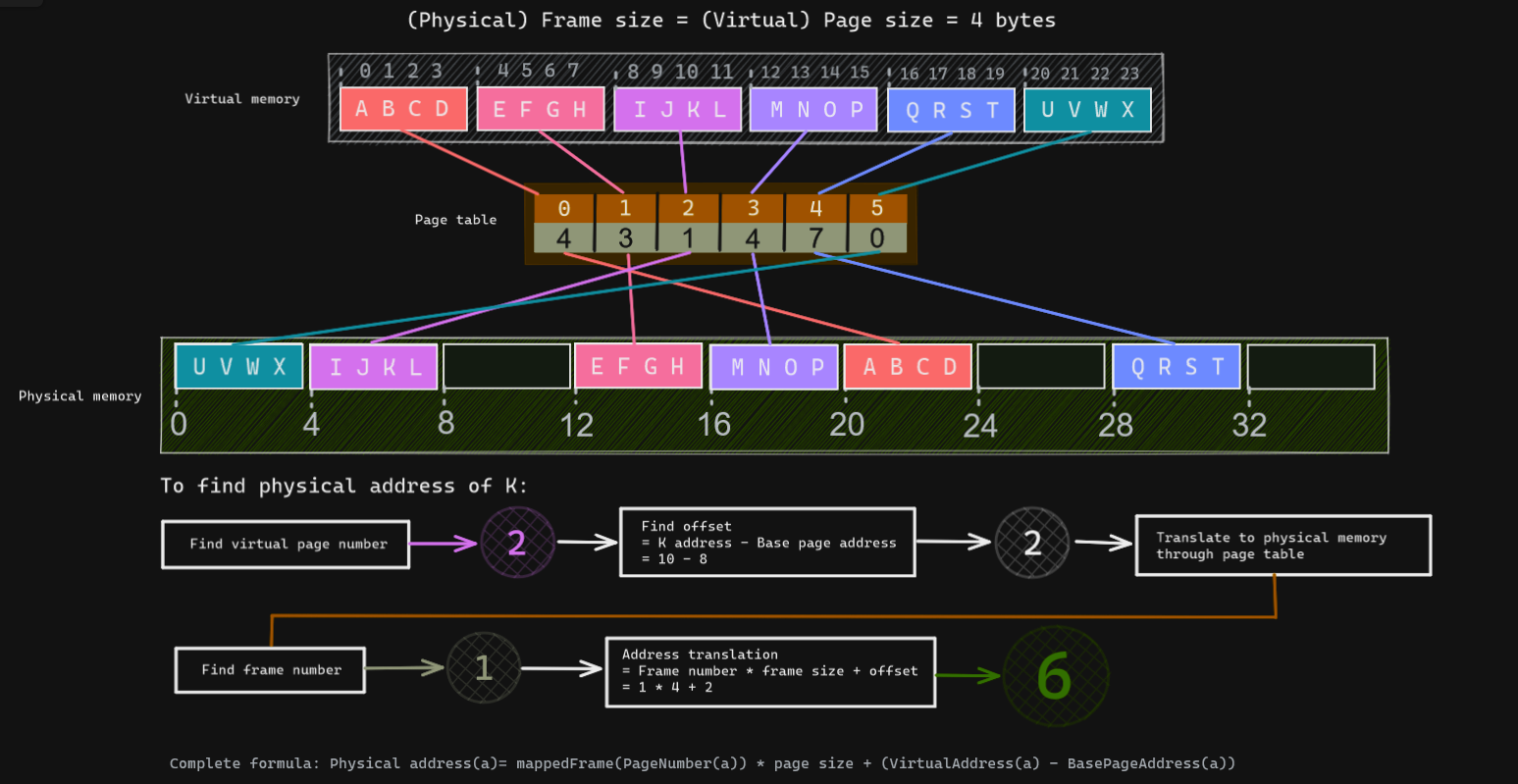

Containers and virtual machines have similar resource isolation and allocation benefits, but function differently because containers virtualize the operating system instead of hardware. This makes containers more portable and efficient. They can be considered a lighter-weight, more agile way of handling virtualization since they don’t use a hypervisor.

To re-use the previous figure, containers run like this:

Containers are an abstraction at the application layer that packages code and dependencies together. They take up less space than VMs (typically tens of MBs in size) and can handle more applications. It is all from the benefits of reducing the operating system redundancy/overhead included in VM. Containerization packages together everything needed to run a single application (along with runtime libraries they need to run). The container includes all the code, its dependencies and even the operating system itself. This enables applications to run almost anywhere.

Containers use a form of operating system virtualization, but they leverage features of the host operating system to isolate processes and control their access to physical devices. While the technology has been around for decades, the introduction of Docker in 2013 changed the common consensus.

Containers are made available through a few Kernel features, mainly: | Kernel features | Description | | — | — | | Kernel namespaces | It wraps a global system resource in an abstraction that makes it appear to the processes within the namespace that they have their own isolated instance of the global resource | | Seccomp | Provides application sandboxing mechanism. It allows one to configure actions to take for matched syscalls | | CGroups (control groups) | Used to restrict resource usage for a container and handle device access. It restrict cpu, memory, IO, pids, network and RDMA resources for the container |

There is a few containers projects to note:

- LXC (System containers without the overhead of running a kernel) - also called Linux containers

- Docker containers (cross-platform, standalone executable packages)

- Snaps (Single machine deployment for fleet of IoT devices)

- Tanzu (VMWare container solution)

It is interesting to note that, while Docker has been synonymous with containers from the beginning, It might change in the coming years. Kubernetes announced last year that they will shift from Docker Runtime to the Container Runtime Interface as defined by the Open Container Initiative, which supports a broader set of container runtimes with smooth interoperability. It will open the way for Docker competitors in the future (or not).

Container manager

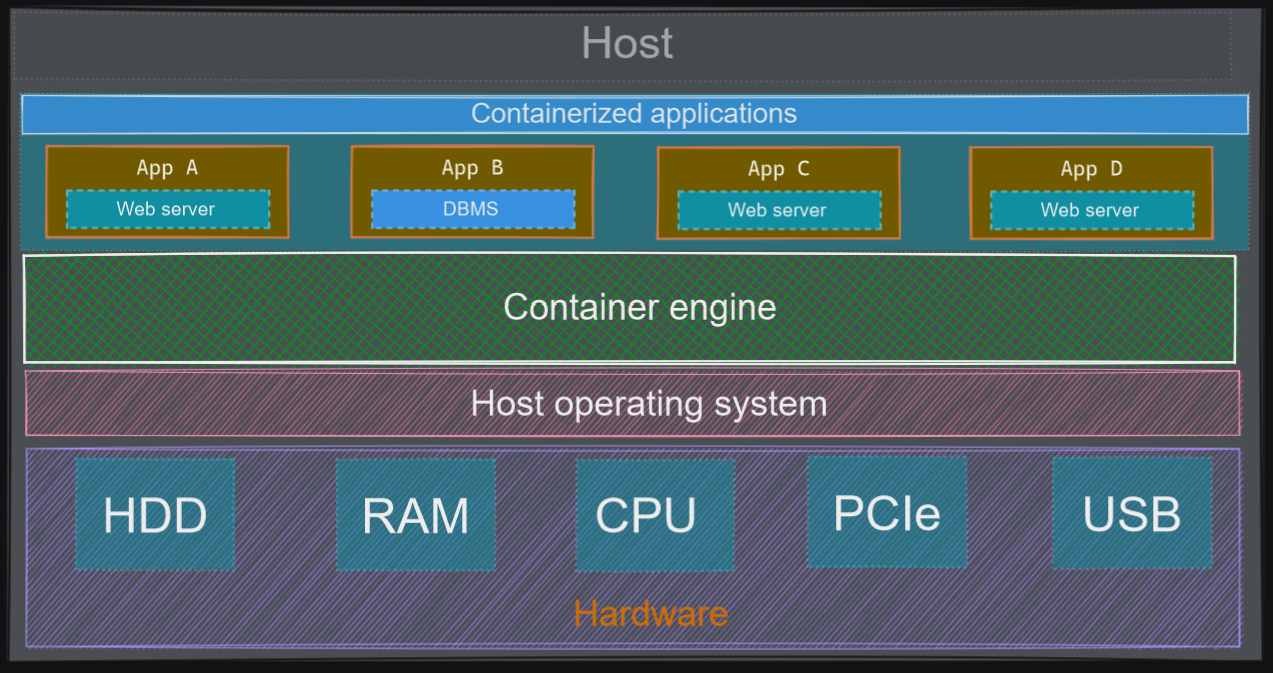

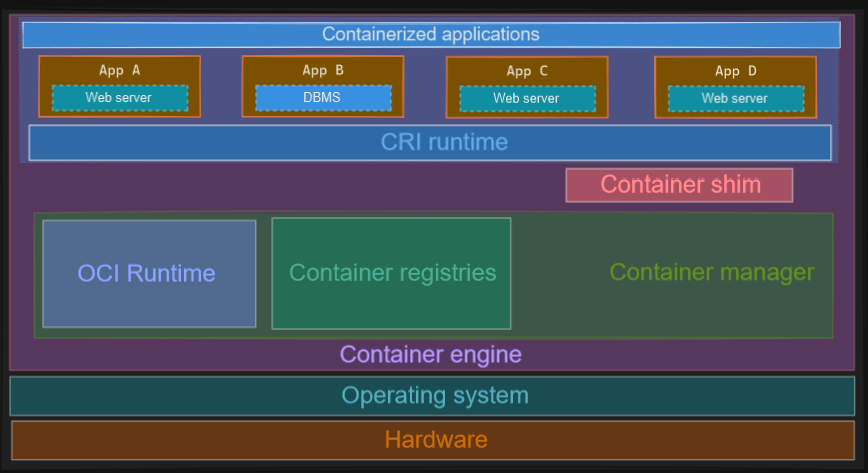

First, check out this containerd architecture:

It gives out a nice top-level overview of how a system (whether It’s Windows or Linux) interact with its containers (whether they are docker, from cloud providers, or from k8s).

Why am I talking about containerd ? Docker (or containers) is a cluster of various utilities doing a wide variety of things hidden under the hood. Simply typing docker run webserver is great for users, but bad to understand its inner architecture. A great article about this is here and this part will simply reflect what I learnt from it.

containerd is meant to be a simple daemon that will manage your containers and shims so they can run on any system. This manager will be the sticking glue between all your containers and the underlying system. It focuses on handling multiple containers so they can co-exist happily. It will handle all the boring part you don’t think of, like :

- Image push and pull support

- Interfaces creation, modification and deletion

- Management of network namespaces containers to join existing ones.

- Storing container logs and snapshots

- Support of container runtime and lifecycle

Picture an apartment building. The hardware and system could be considered the ground, where utilities such as electricity (CPU), water (Storage) and heating (RAM) comes from. The building is the container manager, allowing each unit to co-exist by appointing each resource. Each apartment is the container runtime, that possess its own layout (configuration), and host a tenant. The container is this tenant who will use the available resource to conduct its lifecycle.

Most interactions with the Linux and Windows container feature sets are handled a container runtime, often via runc and/or OS-specific libraries.

Container runtime

Also called OCI runtime, there is a specification for it to specify the configuration, execution environment and lifecycle of a container.

For example, In each container, to name a few specification:

- In the filesystem, the following directory should be available: /proc /sys /dev/pts /dev/shm

- Following devices should be supplied: /dev/null /dev/zero /dev/full /dev/random /dev/tty

- Possess a status which may be : creating created running stopped

- Run through the following lifecycle: Create -> createRuntime -> createContainer -> startContainer -> delete -> poststop

A container runtime can be considered the client part that will interact with its container manager. To start a containerized process, It happens in two steps: we create the container, then we run the process inside it. To create the container, we need to create namespaces (to isolate it from others), configure cgroups (to limit its ressource usage), etc. That’s what the container runtime will do. It knows how to create such boxes and how to interact with them since he created it.

Some folks also call this brick : low-level container runtimes since they only handle container execution. High-level container runtimes would handle image format/management/sharing like containerd does, but It is just confusing, so I prefer to separate them into manager and runtime. It is difficult to name them on high/low scale, because docker runs containerd which runs runc, add a container orchestration tool on top of it, and you are stuck in a maze of naming conventions.

You can even add programs that will stand in-between the container runtime and the container manager, they are called shim.

An architecture top-level overview (correct me If I’m wrong, It’s difficult to place everything correctly.

Linux containers

A container is an isolated (namespaces) and restricted (cgroups, capabilities, seccomp) process.

This phrase recaps what we learned of containers so far, but It is not necessarily true. In theory, they are an isolated and restricted environments to run on or many processes inside. This means projects like Kata implements container without using namespaces or cgroups but full-fledged VMs and be used by Kubernetes for example.

Here, we will focus on the most popular kind of containers, which are Linux containers. Here we could use LXC to illustrate it, but let’s not forget that It is a set of user-land utilities, we can just try to use kernel features instead to reproduce it (not as well of course).

Let’s create a cgroup and launch an application inside. Since we will be using kernel features, I will use root user for simplification.

Let’s define what I want to run: </dev/zero head -c 6G | tail - It will fill 6G of RAM on the system

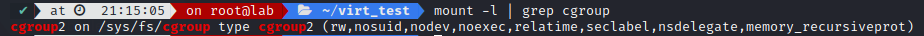

I’m using cgroups v2 for this, be sure to check what your kernel version has with:

The following script took me a few hours, as I had to realllyy read the kernel documentation on cgroups v2. Main issue was the No internal Process Constraint which make it so when you want to create a new cgroup and switch process inside it, you have to start from the root cgroup, because starting from any other cgroup requires you to switch all your running processes into the newly created one before doing anything (like adding memory control onto its subtree_control file).

The script switch your shell into the root cgroup, run the command, switch the process into our new cgroup, limits RAM to 2G let it run for a few seconds (even though It should go up to 6G), you will notice how the memory will not go higher than 2G and will slowly start to fill in the swap space before we end it. It then re-switch back to the original cgroup. It’s not perfect of course, feel free to comment on it.

The code :

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

#!/bin/sh

## ASSUMES CGROUPSv2

# Store current cgroup

shell_pid=$$

stored_cgroup="$(cut -d":" -f3 "/proc/$shell_pid/cgroup")"

switched_cgroup=false

# if we are not already inside / cgroup, switch us

if ! grep "\b$shell_pid\b" "/sys/fs/cgroup/cgroup.procs" > /dev/null; then

printf "[I] Switching shell from %s cgroup to root cgroup\n" "$stored_cgroup"

echo "$shell_pid" > "/sys/fs/cgroup/cgroup.procs"

switched_cgroup=true

else

printf "[I] Already in root cgroup\n"

fi

cgroup_name="cg_test"

cgroup_dir="/sys/fs/cgroup/$cgroup_name"

byte_memory_input=6442450944 # 6 GB

byte_memory_limit=2147483648 # 2 GB

if [ ! -d $cgroup_dir ]; then

mkdir $cgroup_dir

else

printf "[I] %s already exist\n" "$cgroup_dir"

fi

# Specify we want memory

if [ $(grep -i "memory" "$cgroup_dir/../cgroup.controllers" | wc -l) -eq 1 ]; then

if [ ! $(grep -i "memory" "$cgroup_dir/../cgroup.subtree_control" | wc -l) -eq 1 ]; then

printf "[E] Missing memory in subtree parent control cgroup\n"

exit 1

fi

printf "[I] Memory is available on parent cgroups, we can add limit on our cgroup\n"

else

printf "[E] Memory unavailable on cgroups, check parent available resources in $cgroup_dir, exiting..\n"

exit 1

fi

## BE CAREFUL TO NOT ADD ANYTHING INTO OUR NEWLY CREATED CGROUP SUBTREE_CONTROL

## See https://www.kernel.org/doc/html/latest/admin-guide/cgroup-v2.html#no-internal-process-constraint

## It makes it impossible to add any process to our cgroup, since It stops being a leaf

# Add our memory limit to the cgroup

# memory.high is the memory usage throttle limit

# memory.max is the memory usage hard limit, going beyond invokes OOM grimreaper

if [ -f "$cgroup_dir/memory.high" ]; then

printf "[I] Adding memory limit of %s to our cgroup\n" "$byte_memory_limit"

echo "$byte_memory_limit" >> "$cgroup_dir/memory.max"

else

printf "[E] Missing %s\n" "$cgroup_dir/memory.max"

printf "[E] Unable to add memory limit, exiting..\n"

exit 1

fi

# Now that our cgroup is created with a memory limit

# We need to execute our program in its namespace and add its PID to our cgroups

</dev/zero head -c $byte_memory_input | tail &

process_pid=$!

printf "[I] Created memory command at %s\n" "$process_pid"

printf "[I] Currently executing in cgroup %s\n" "$(cut -d":" -f3 "/proc/$process_pid/cgroup")"

printf "[I] Adding PID %s to %s/cgroup.procs\n" "$process_pid" "$cgroup_dir"

printf "[I] Switching process to our new cgroup %s\n" "$cgroup_name"

echo "$process_pid" >> "$cgroup_dir/cgroup.procs"

#

# Sleep for a bit, not necessary but better to read what's going on

printf "[I] Going to sleep while you read this\n"

sleep 15

printf "[I] Killing memory process as test is over\n"

kill -9 "$process_pid"

printf "[I] Kill successfull, exiting soon\n"

if [ "$switched_cgroup" = true ]; then

printf "[I] Switching back to original cgroup %s\n"

echo "$shell_pid" > "/sys/fs/cgroup$stored_cgroup/cgroup.procs"

printf "[I] Now running shell in cgroup: %s\n" "$(cut -d":" -f3 "/proc/$shell_pid/cgroup")"

else

printf "[I] We were already in root cgroup, just exiting without switching\n"

fi

exit 0

The result:

Feel free to add namespaces on top of it, use unshare command to add it

The next step

The technology is still very new, as demonstrated with the google trends of Docker and K8:

There is still many work to do in order to ensure containers monitoring, provisionning and orchestration. They are indeniably the way we will package applications in the future, as It is much more adaptable to a Cloud environment where hardware requires to be elastic to answer a growing organization needs.

Conclusion

This concludes the introduction to virtualization as a concept. While I did not dive into the different linux technologies such as QEMU or Virt-lib, I was much more interested in understanding how IOMMU was working at the hardware level. I tried to avoid including too many details, and stayed with a top-level overview of each concepts. It’s a bit difficult to understand how they work architecturally, as many articles focus more on the code structure, or options. I’m happy with the page translation drawing I did, as It was not something clear to me for a long time. I hope It helped into understanding how virtualization is used, and how It will continue to evolve over the next decade.

Credits

https://www.citrix.com/fr-fr/solutions/vdi-and-daas/what-is-hardware-virtualization.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/X86virtualization#I/O_MMU_virtualization(AMD-Vi_and_Intel_VT-d)

https://lenovopress.com/lp1467.pdf

https://www.cs.cornell.edu/courses/cs4410/2016su/slides/lecture11.pdf

https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/linux-device-drivers/0596005903/ch15.html

https://www.kernel.org/doc/html/latest/core-api/dma-api-howto.html

https://www.infrapedia.com/app

https://ubuntu.com/blog/what-is-virtualisation-the-basics

https://www.docker.com

https://containerd.io

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sK5i-N34im8 // cgroups,namespaces and beyond: what are containers made from ? By J. Petazzoni

https://jvns.ca/blog/2016/10/10/what-even-is-a-container/

https://iximiuz.com

http://slides.com/chrisdown/avoiding-bash-pitfalls-and-code-smells